Dementia Action Week

18-24 September

Australian Dementia facts and statistics

Updated March 2023

Dementia is the second leading cause of death among Australians and provisional data is showing that dementia will likely soon be the leading cause of death. - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Dementia is the leading cause of death for women. - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Dementia in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 January 2023.

In 2023 it is estimated that there are more than 4000 000 Australians living with dementia. Without a medical breakthrough, the number of people with dementia is expected to increase to more than 800,000 by 2058.- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

In 2023, it is estimated there are more than 28,650 people with younger onset dementia expected to rise to more than 42,400 people by 2058. This can include people in their 30s, 40s and 50s. - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

In 2023, it is estimated that more than 1.5 million people in Australia are involved in the care of someone living with dementia. - Department of Health and Aged Care.

2 in 3 people with dementia are thought to be living in the community.

More than two-thirds (68.1%) of aged care residents have moderate to severe cognitive impairment. - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Economic cost - The total cost of Dementia in Australia in 2016, was $14.25 billion which equated to an average cost of $35,550 per person with dementia.

To download the key facts and statistics pdf file, click here.

What is Dementia?

Dementia is the umbrella term for a number of neurological conditions, of which the major symptom includes a global decline in brain function. - Dementia Australia

Early signs and symptoms of dementia are subtle and may not be immediately obvious.

Common symptoms include:

memory loss

changes in planning and problem-solving abilities

difficulty completing everyday tasks

confusion about time or place

trouble understanding what we see (objects, people) and distances, depth and space in our surroundings

difficulty with speech, writing or comprehension

misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps

decreased or poor judgement

withdrawal from work or social activities

changes in mood and personality

The causes of dementia are unknown.

How is dementia diagnosed?

A number of conditions produce symptoms similar to dementia. These can often be treated. They include some vitamin and hormone deficiencies, depression, medication effects, infections and brain tumours.

It is essential to talk to your doctor when symptoms first appear. If you feel comfortable, take a relative or friend with you.

If the symptoms are caused by dementia, an early diagnosis means early access to support, information and, if it is available, medication.

If symptoms are not caused by dementia, early diagnosis will be helpful to treat other conditions.

Who gets dementia?

Did you know that dementia can happen to anybody, but the risk increases with age?

Genetics, lifestyle and health factors are associated with an increased risk of developing dementia.

In a few cases, Alzheimer’s disease is inherited, caused by a genetic mutation.

This is called familial Alzheimer’s disease, with symptoms occurring at a relatively young age. This is usually when someone is in their 50s, but sometimes younger.

Over the age of 65, dementia affects almost 1 in 10.

Over the age of 85, dementia affects 3 in 10.

We often associate old people from having dementia, where in fact dementia is not a normal part of ageing.

What causes dementia?

There are 4 common forms of dementia?

Alzheimer’s disease

Vascular dementia

Lewy body disease

Frontotemporal dementia

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia.

Disrupts the brain’s neurons, affecting how they work and communicate with each other.

‘It affects how they work and communicate with each other. A decrease of important chemicals stops messages travelling normally through the brain.

People with Alzheimer’s disease experience different challenges and changes throughout the progression of the condition.

An individual’s abilities deteriorate over time, although the progression varies from person to person.

Signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease

Symptoms may include:

• persistent and frequent short-term memory loss, especially recalling more recent events

• repeatedly saying the same thing

• vagueness in everyday conversation

• changes in ability to plan, problem solve, organise and think logically

• taking longer to do routine tasks

• language and comprehension difficulties, such as problems finding the right word

• increasing disorientation in time, place and person

• problems in becoming motivated and initiating tasks

• changes in behaviour, personality and mood.

Someone experiencing symptoms may be unable to recognise any changes in themselves.

Often a family member or friend of someone affected will observe changes in a person.

Symptoms vary as the condition progresses and as different areas of the brain are affected. A person’s abilities may fluctuate from day to day, or even within the same day. Symptoms can worsen in times of stress, fatigue or ill-health.

What causes Alzheimer’s disease?

Apart from the few people with familial Alzheimer’s disease, it is not known why some people develop Alzheimer’s disease and others do not.

Like with so many chronic diseases, health and lifestyle factors that may contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease include:

• physical inactivity

• lack of mental exercise

• smoking

• obesity

• diabetes

• high cholesterol

• high blood pressure.

How Alzheimer’s disease progresses

The deterioration progression over time varies from person to person.

‘As Alzheimer’s disease affects different areas of the brain, specific functions or abilities are lost. Short-term memory is often the first to be affected, but as the disease progresses, long-term memory is also lost.

The disease also affects many of the brain’s other functions and consequently language, attention, judgement and many other aspects of behaviour are affected.

Some abilities remain, although these lessen as Alzheimer’s disease progresses.

People living with advancing dementia may keep their senses of touch and hearing, and also respond to emotion even in the advanced stages of the condition.

At the end stages of Alzheimer’s disease many people become immobile and dependent, requiring extensive care.

There are 3 stages or phases of Alzheimer’s disease.

Not all these features will be present in every person, and they might occur at different stages.

Mild Alzheimer’s disease

The onset of Alzheimer’s disease is usually gradual, and it is often impossible to identify exactly when it began.

Someone might:

• appear more apathetic

• lose interest in hobbies and activities

• be less willing to try new things

• be less able to adapt to change

• be slower to grasp complex ideas and take longer with routine jobs

• become more forgetful of recent events

• become confused or disoriented to time and place

• become lost if away from familiar surroundings

• be more likely to repeat him/herself or lose the thread of their conversation

• be more irritable or upset if a mistake is made

• have difficulty managing finances

• have difficulty shopping or preparing meals.

2. Moderate Alzheimer’s disease

At this stage, the impacts of the condition are more apparent and prevalent.

A person may experience significant challenges to their independence and require daily support.

Someone might:

• be forgetful of current and recent events, although generally remember the distant past, even if details may be forgotten or confused

• often be confused regarding time and place

• become lost more easily

• forget the names of family or friends, or confuse family members

• forget saucepans or kettles left heating on the stove

• be less able to perform simple calculations

• show poor judgement and make poor decisions

• see or hear things that are not there or become suspicious of others

• become repetitive

• neglect personal hygiene or eating

• be unable to choose appropriate clothing for the weather, occasion or time of day

• become angry, upset or distressed through frustration.

3. Advanced Alzheimer’s disease

At this stage, the person is severely impacted by dementia and needs continuous care for all daily activities.

Someone might:

• be unable to remember current or recent events, such as forgetting that they have just eaten, or being unable to recall where they live

• be unable to recall important events or facts from their early life

• be confused trying to recognise friends and family

• fail to recognise everyday objects or understand their purpose

• lose their ability to understand, or to speak

• need help eating, washing, bathing, brushing their teeth, toileting and dressing

• become incontinent

• experience disturbed sleep

• be restless or fidgety

• call out frequently or have aggressive outbursts

• have difficulty walking and other movement problems, including rigidity.

Treatment and management options: -

At present there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease and no treatment can stop the condition progressing.

However, medications can help stabilise or slow the decline in memory and thinking abilities.

Drugs may also be prescribed for secondary symptoms such as agitation or depression, or to improve sleep.

Non-drug therapies can be beneficial, such as staying active and socially connected, and managing stress.

Talking to a counsellor or psychologist is important to help manage changes in behaviour and mood.

Occupational therapy can help improve everyday functioning at home.

At all stages of Alzheimer’s disease, treatments and support services are available to reduce the impact of symptoms, to ensure the best possible quality of life for every person living with the condition.

For a copy of this help sheet about Alzheimer’s disease, click here.

2. Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia is a form of dementia caused by brain damage resulting from restricted blood flow in the brain.

It affects someone’s thinking skills: such as reasoning, planning, judgement and attention.

Changes in skills and abilities are significant enough to interfere with daily social or work functioning.

Often vascular damage occurs alongside Alzheimer’s disease or other brain disease. - Dementia Australia.

Causes of vascular dementia

Vascular dementia can be caused by:

• a single large stroke

• multiple strokes

• untreated high blood pressure or diabetes leading to vascular disease in the small blood vessels deep within the brain.

The location and size of brain damage determines which brain functions are affected.

There are 3 types of vascular dementia namely:

a - Strategic infarct dementia

b - Multi-infarct dementia

c - Subcortical vascular dementia

Strategic infarct dementia

One single large stroke can sometimes cause vascular dementia, depending on the size and location of the stroke.

Strategic infarct dementia is characterised by the sudden onset of changes in thinking skills or behaviour.

Symptoms vary depending on the location of the stroke and what brain functions it affected.

Provided no further strokes occur, the person’s symptoms may remain stable or even improve over time. However, if there is other vascular disease also affecting the brain or additional strokes occur, symptoms may worsen.

b - Multi-infarct dementia

This type of dementia is caused by multiple strokes.

It is associated with disease of the brain’s large blood vessels.

Often the person does not notice symptoms when the strokes occur.

Over time, as more strokes occur, more damage is done to the brain, with reasoning and thinking skills affected to the point that a vascular dementia diagnosis is made.

Depending on the location of the brain damage, other symptoms can include depression and mood swings.

After each new stroke, symptoms can worsen, then stabilise for a while.

c - Subcortical vascular dementia

Where Multi-infarct dementia is associated with disease of the brain’s large blood vessels, Subcortical vascular dementia is associated with disease in the small blood vessels deep within the brain and damage to subcortical (or deep) areas of the brain.

It can be caused by untreated high blood pressure or diabetes leading to vascular disease.

Symptoms often include:

deterioration of reasoning and thinking skills

mild memory problems

walking and movement problems

behavioural changes

lack of bladder control.

Subcortical vascular dementia is usually progressive, with symptoms worsening over time as more vascular damage occurs.

Diagnosing vascular dementia

No single specific test can diagnose vascular dementia.

A diagnosis is based on the presence of dementia, with vascular disease being the most likely cause of the symptoms.

If vascular dementia is suspected, medical tests will be carried out.

These may include:

an assessment of changes in thinking and behaviour, and how they are affecting daily function

a full medical history

blood tests

a neurological examination (testing reflexes, senses, coordination and strength)

neuropsychological tests (assessing changes in thinking abilities)

brain imaging (to detect abnormalities caused by strokes or blood vessel disease)

carotid ultrasound (to check for damage in the carotid arteries).

Vascular dementia can be very difficult to distinguish from other forms of dementia, because the symptoms of each type overlap. Also, many people with dementia have both vascular disease and other brain conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, and therefore have a mixed dementia.

Who gets vascular dementia?

Vascular dementia can happen to anyone, but the risk increases with age.

Health and lifestyle factors can also increase the risk of vascular dementia, including:

• high blood pressure

• high cholesterol

• diabetes

• obesity

• smoking

• physical inactivity and poor diet

• heart rhythm abnormalities

• heart disease

• blood vessel disease

• history of multiple strokes.

Treatment and management options

There is no single treatment for vascular dementia.

• If the dementia is stroke-related, treatment preventing additional strokes is important.

• A healthy diet, exercise and not smoking may reduce the risk of further strokes or vascular brain damage.

• Medications for treating Alzheimer’s disease may be effective for some people to improve memory, thinking and behaviour.

• Occupational therapy can help someone adapt to changes in abilities and stay independent.

Controlling conditions that affect the underlying health of your heart and blood vessels can sometimes slow the rate at which vascular dementia worsens and may also sometimes prevent further decline.

• Prescribed medications can control high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease and diabetes.

• Aspirin or other drugs may be prescribed to prevent clots from forming in blood vessels.

For a copy of this help sheet about Vascular dementia, click here.

3. Lewy body disease

‘Lewy body disease is a term that incorporates both Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, which share similarities in the ways by which they both damage the brain at the cellular level and in the symptoms a person may experience.

Lewy bodies are microscopic structures that can be seen inside some of the brain cells of people diagnosed with both Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. The Lewy body is composed of a protein called alpha-synuclein that, for reasons that are not understood, becomes disrupted and tangled.’ - Dementia Australia

Forms of Lewy body disease.

‘There are 3 overlapping disorders, namely:

Parkinson’s disease, which is diagnosed by the presence of significant movement symptoms including slowness, muscle stiffness and tremor.

Parkinson’s disease dementia, which is diagnosed when a person develops dementia symptoms after having at least 12 months of established Parkinson’s disease. The progression from Parkinson’s disease to Parkinson’s disease dementia can be slow.

Dementia with Lewy bodies, a prominent feature of which is the presence of dementia symptoms at least 12 months before the development of the significant movement symptoms that are prominent in Parkinson’s disease.

These movement symptoms are known as ‘Parkinsonism symptoms’ but not everyone who has dementia with Lewy bodies will develop them and not everyone will be diagnosed as having Parkinson’s disease.’

Signs and symptoms of Lewy body disease

Along with the symptoms described above, other health conditions may indicate the presence of Lewy body disease. These include:

apathy

anxiety

depression

fainting

constipation

urinary incontinence

excessive sleepiness

poor sense of smell

delusions.

Symptoms will depend on which the area of the brain is affected and disease progression.

Diagnosing Lewy body disease

A full assessment may include:

a medical history from the person

an interview with a family member

blood tests

tests of cognitive abilities

brain imaging

other medical tests as requested by a doctor or medical specialist.

Even with these tests, a definitive diagnosis may not be possible at the first assessment.

Getting a diagnosis can be more challenging when the physical signs are not as evident.

Often the person with symptoms:

may not agree with the concerns of others

may present as being unaffected at a doctor consultation

can perform well on initial cognitive screening tests, such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE).

A ‘watch and review’ plan is sometimes suggested, or medication is offered for the most pressing health issue.

Dementia Australia recommends to ‘assist the specialist, consider writing a diary of behaviours and actions of the person one week before the appointment, noting changes in behaviour, thinking and abilities that may be regarded as out of character for the person or troubling to the person or you. Reference days and times to indicate how often changes are present or not, for how long when present, and how frequently they change.

For a copy of this help sheet about Lewy body disease, click here.

4. Frontotemporal dementia

Dementia describes a collection of symptoms caused by disorders affecting the brain. - Dementia Australia.

Frontotemporal dementia causes progressive damage to either or both the frontal or temporal lobes of the brain.

Early symptoms affecting the frontal lobe are often behavioural symptoms and personality changes.

Early symptoms affecting the temporal lobe involve changes to speech and comprehension.

Memory often remains unaffected, especially in the early stages of the condition.

Frontotemporal dementia is more commonly diagnosed in people under the age of 65’.

Signs and symptoms of frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia is progressive and affects everyone differently. This means that symptoms may be mild at first but will worsen over time.

There are several different types of frontotemporal dementia, with symptoms depending on which areas of the brain are affected first.

Each type of frontotemporal dementia, namely: -

Behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia,

Primary progressive aphasia,

Semantic dementia,

Progressive non-fluent aphasia, each with their owns signs and symptoms.

Behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia

The main changes seen are in personality and behaviour, known as behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia.

The areas of the brain that control conduct, judgement, empathy and foresight are damaged.

Symptoms vary from person to person, depending on which areas of the frontal lobes are damaged. Some people become apathetic, while others become disinhibited; some may alternate between apathy and disinhibition.

Common symptoms can include:

fixed mood and behaviour, appearing selfish and unable to adapt to new situations

loss of empathy, emotional warmth and emotional responses towards others

apathy or lack of motivation, abandoning hobbies or avoiding social contact

loss of normal inhibitions, talking to strangers or exhibiting embarrassing behaviour

difficulty in reasoning, judgement and planning

being easily distracted or impulsive

changes in eating patterns, such as craving sweet foods, overeating, or unusual food preferences

a decline in self-care and personal hygiene

lack of insight

repetitive motor (physical) behaviours such as collecting, counting and tapping.

Primary progressive aphasia

When the temporal lobes are affected first, there is a loss of language skills: this is known as primary progressive aphasia. Other aspects of thinking, perception and behaviour are not affected as much in the early stages.

Semantic dementia

Semantic dementia is a temporal variant, where the ability to assign meaning to words, to find the correct word, or to name people and objects is gradually lost. Reading, spelling, comprehension and expression are usually unaffected.

Symptoms of semantic dementia include:

gradually losing a range of vocabulary, using more general words instead

losing the ability to understand single words, especially uncommon ones

difficulty finding the right word, or someone’s name

forgetting what familiar objects are used for, or being unable to name them.

However, grammar and the ability to speak fluently remain, so someone with the condition may sound fluent, but their speech may lack meaning.

Many people with semantic dementia retain other functional abilities (such as decision-making or motor skills) and can undertake activities of daily living until very late in the disease. Changes in behaviour may also be present, such as becoming obsessed about daily routines and emotional responses.

Progressive non-fluent aphasia

A person will have problems with speaking and, over time, will lose their ability to speak fluently.

Symptoms vary, but include:

speaking differently, producing words slowly, stuttering or having slurred speech

remaining articulate, but saying the wrong word, using incorrect grammar or using shorter or incomplete phrases

difficulty following conversations, communicating with groups of people, or using the telephone

a declining ability to read and write.

Overlap with motor disorders

A small number of people affected by frontotemporal dementia also develop conditions that affect their movement. Motor symptoms can occur either before or after the symptoms of dementia first appear.

These conditions are relatively rare, but include motor neurone disease and other movement disorders such as corticobasal syndrome and progressive supranuclear palsy.

What causes frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia is caused by brain disease, but why some people get it is unknown (except in familial frontotemporal dementia, which is caused by a gene mutation).

Who gets frontotemporal dementia?

Frontotemporal dementia can affect anyone.

Symptoms of frontotemporal dementia typically occur between the ages of 40 and 65, though it can affect people younger or older than this.

Almost a third of people with frontotemporal dementia have a family history of dementia. However, only about 10 to 15% per cent of people with the condition have familial frontotemporal dementia caused by a gene mutation. The genetic basis of the condition is not fully understood and is being researched.

Diagnosing dementia

It is important that someone with suspected frontotemporal dementia is assessed by a neurologist, geriatrician or psychiatrist specialising in dementia.

A typical assessment includes:

• a detailed medical history from the person

• a conversation, if possible, with a close family or carer who has observed symptoms, when they began and how often they occur

• a physical examination

blood and urine tests

• a psychiatric assessment

• a neurological assessment (tests of cognitive abilities such as comprehension and problem-solving)

• brain imaging (MRI).

Treatment options

Currently there are no treatments available to cure or slow disease progression, but several clinical trials are currently underway in Australia and around the world.

Various therapies can help with some of the symptoms, such as changes in behaviour and language.

• Talking to a counsellor or psychologist is important to help manage changes in behaviour and mood.

• Occupational therapy can help improve everyday functioning at home.

• Speech therapy can help people with semantic dementia and progressive non-fluent aphasia to develop alternative communication methods.

Secondary symptoms such as depression or sleep disturbances may be helped by medication.

Learning more about frontotemporal dementia and its impacts on the brain can help others to understand why someone is behaving in a particular way. With support, family members and carers can develop strategies to support someone impacted by behavioural and psychological symptoms.

How frontotemporal dementia progresses.

Frontotemporal dementia is a terminal illness.

As the disease progresses, additional areas of the brain may be affected.

It causes progressive and irreversible decline in a person’s abilities over a number of years.

Reducing your risk of dementia

When we reach middle age, there are changes that start to happen in our brain.

Aspects that cannot be changed like:

Age - as we age, the risk of developing dementia increases.

Genetics - ‘there are a few very rare forms of dementia associated with specific genes

Family history – a family history of dementia increases your risk of developing dementia but at this stage, it is not clear why.

Things that can be changed through lifestyle choices by looking after the following:

Your heart

Your body and

Your mind

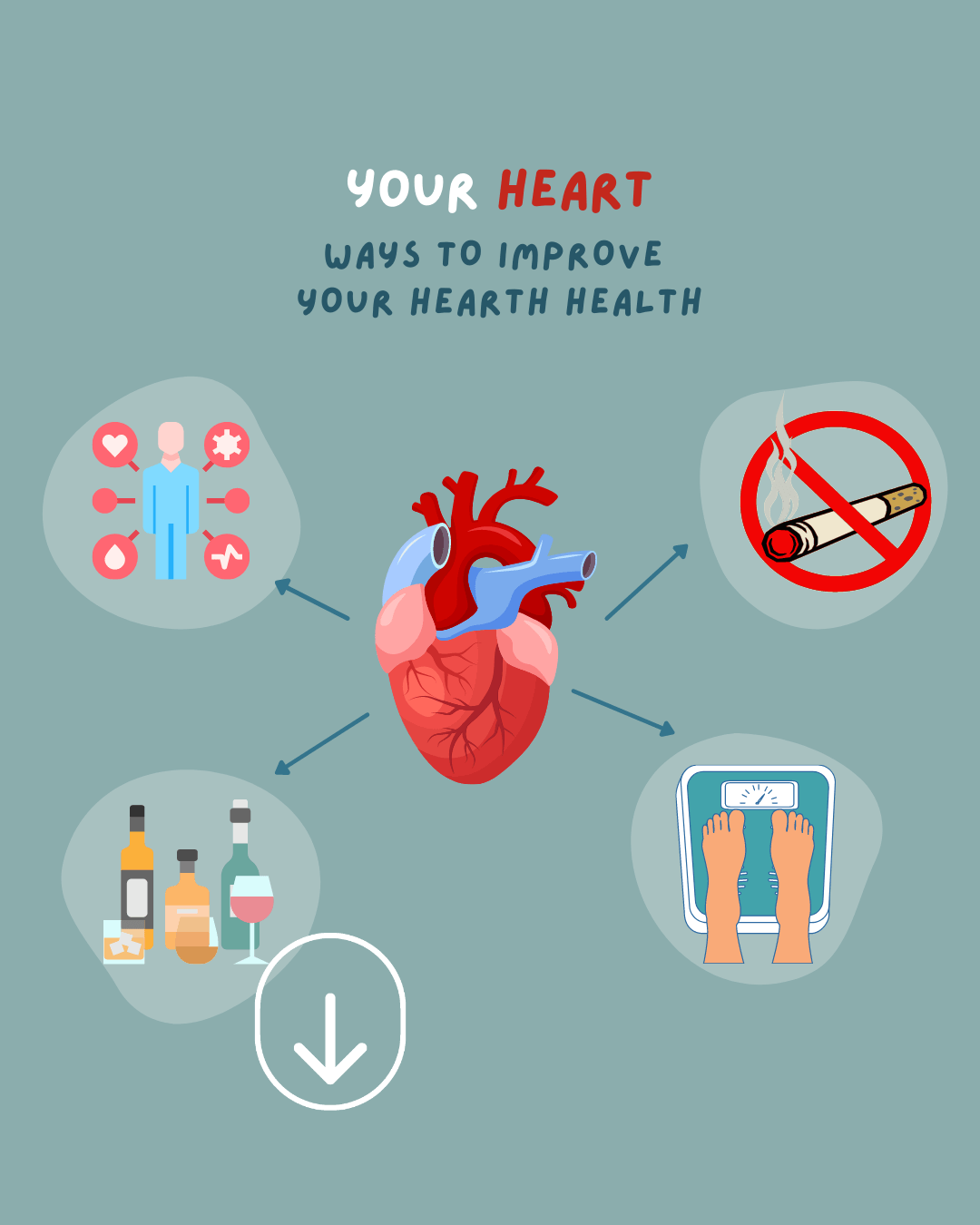

1. Your heart

Looking after your heart.

Many people are unaware of the connection between heart health and brain health.

The latest research shows that cardiovascular conditions are linked to a higher risk of developing dementia later in life.

These conditions include: -

High blood pressure

High cholesterol

Type 2 diabetes

Obesity

Heart disease

Smoking

Ways to improve your heart health.

Get regular health checkups like monitoring your blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar level.

Stop smoking. It affects both the heart and brain.

Limit alcohol intake to 2 standard drinks a day or at least 2 alcohol-free days per week. ‘Excessive drinking can result in brain damage over time and produce symptoms of dementia.

Maintain a healthy weight.

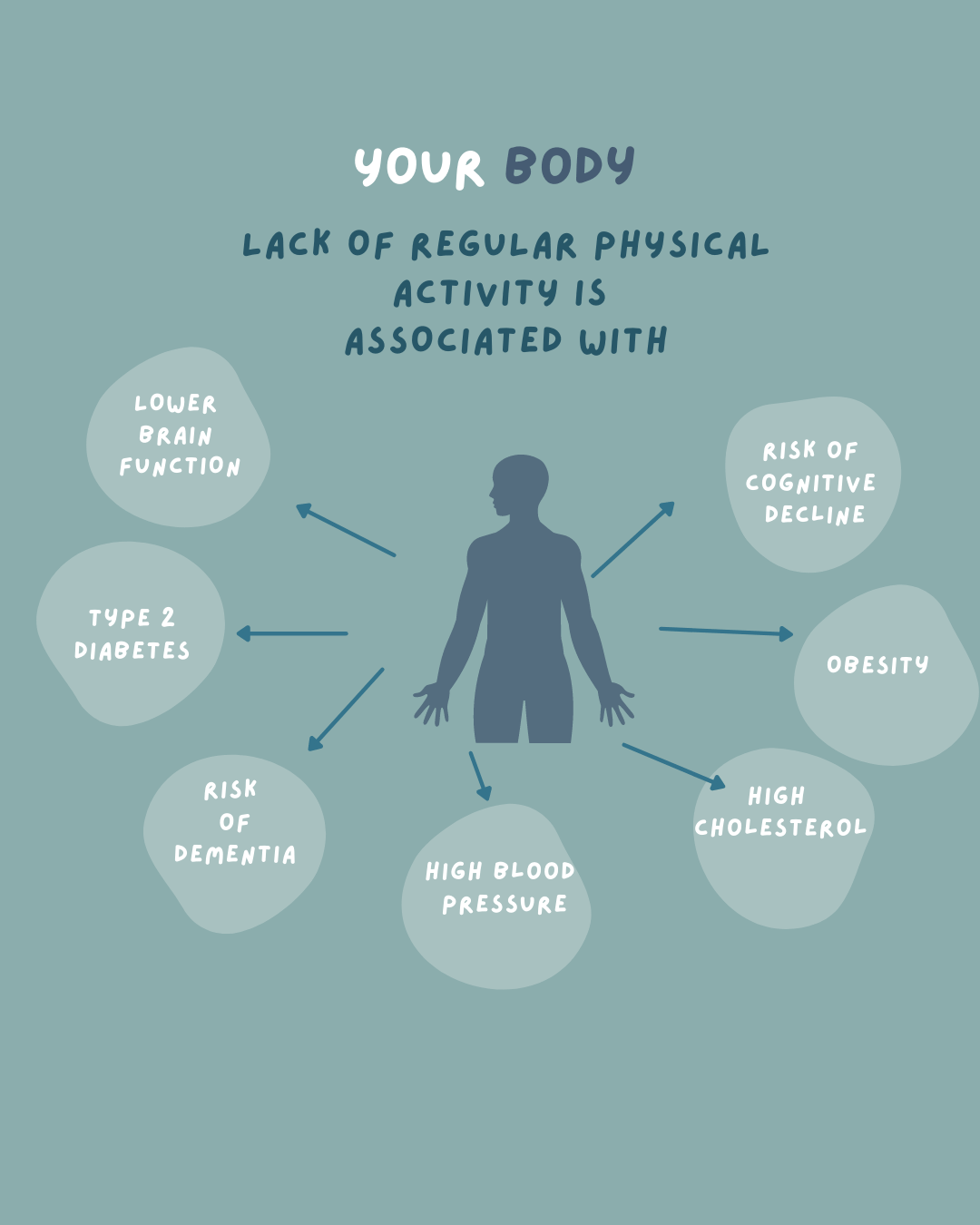

2. Your body

We know that exercise is good for our body and that it may reduce our risk in preventing certain diseases and some cancer. But did you know that ‘Your risk of developing dementia may increase if you don’t look after your physical fitness and health?’

Exercise increases the blood flow to the brain and ‘stimulates the growth of brain cells and the connections between them’.

Diet,

Sleep patterns,

Hearing and head protection are also factors for good body health.

Dementia Australia continues on saying that the ‘Lack of regular physical activity is associated with:

Lower brain function

Risk of cognitive decline

Risk of dementia

High blood pressure

Obesity

High cholesterol

Type 2 diabetes

Here are some suggested ways to look after your body:

ESSA-Exercise-for-Older-Adults-eBook_2020.pdf (exerciseright.com.au)

Follow the National Physical Activity Guidelines for exercise

Follow the Australian dietary guidelines to eat well

Adopt healthy sleeping practices

Look after your hearing and get your hearing checked in mid-life

Protect your head.’

Look after your mind

Keeping your brain active is important to keep it functioning well.

Mental exercise helps to build new brain cells and strengthen connections between them. This helps to give the brain more ‘reserve’ or ‘back up’ so that it can cope better and keep working properly if any brain cells are damaged or die.

Depression

Depression is often associated with an increased risk of dementia. It is important to seek medical advice should you recognise the symptoms of depression and look after your psychological well-being.

There are many ways to look after your mind:

Stay social, enjoy the company of others

Play games like puzzles, crosswords and card games

Learn a new language

Take up a new sport

Learn a new hobby like painting, sewing, woodwork and cooking

Vary your daily activities

If you would like to read more about a ‘Healthy brain, healthy life’, click here.

How to support those living with dementia

Raise awareness

Home life

Initiative

Technology

Be respectful

Health

Listen

Communicating

1 Raise awareness

By being educated and understanding what it’s like having dementia or living with someone with dementia. What’s that expression, ‘Walk the mile in someone’s shoes …”

“People living with dementia are regularly told they ‘don’t look like they have dementia’ because they don’t present, speak, or act in a way the community expects.

What people can’t see they don’t understand and what they don’t understand they tend to avoid.

Often ‘discriminatory’ behaviour is unintended and comes from a lack of understanding about dementia”. We don’t know what we don’t know, till we don’t know what we don’t know.

2. Home life

I’ve read about dementia villages will sensory gardens, with areas of different colours, but never clearly understood just how much this affects someone with dementia.

After reading about the 4 types of dementia and how it affects the brain, I now understand that making these changes can help navigate their way from area to area, room to room. I think this is brilliant.

These changes include the following:

‘Use a D shape door handle that contrasts with the door to ease access

Contrast the colour of doors to the surrounding walls

Consider painting the architraves or door frame a contrasting colour

Consider having the toilet door a different colour from other doors

Consider symbols or photographs to indicate the function of the room

Use either Arial or Helvetica fonts for door signage. Place signage at a 1.2-metre height so they can be easily seen

Ensure contrast in light sockets. You can also put coloured tape around the switch to assist with identification

Use larger switches for turning on and off

Use a whiteboard or calendar to post notes and reminders.

If you need more help with how you can create a better home environment room by room, click here for a home plan which takes you room by room with tips on how you can improve that room.

3. Initiative

Dementia Australia states that ‘Just because someone lives with dementia doesn’t mean they can’t have an active and independent social life.

Focus on the abilities and strengths of the person, not what they can’t do. Value the contributions they make and keep them included where they would like to be.

4. Technology

There are many technological aids and devices available that can make things easier for people living with dementia.

5. Be respectful

Remember the person with dementia is the same person, just different.

6. Health

7. Listen

In a busy world with technology at our fingertips, the greatest gift you can give to someone with dementia is to be present, to listen and for them to be heard.

8. Communicating

One of the most frustrating aspects of dementia includes ‘finding the right word and keeping up with the conversation’.

To know how to talk to someone with dementia go to this very handy pdf for some more tips.

9. Taking initiative

‘Living with dementia doesn’t mean you can’t have an active and independent social life. Stay socially connected to avoid feeling isolated.

Further help

Call the National Dementia Helpline on 1800 100 500.

Watch video about different forms of dementia.

For information, advice, common sense approaches and practical strategies on the topics most commonly raised about dementia, read their Help Sheets.

I know that this all sounds rather daunting. But if we can do everything in our power to prevent dementia; by taking better care of our body, heart, and mind, then at least we have a fighting chance. What do you think? Worth a go?